During the mid 1930's, the possibility of a Second World War with Germany was looking more and more real, in anticipation of this the British Government began its rearmament programme and the "Shadow Factory Scheme". The Shadow Factories were to implement additional manufacturing capacity for the British aircraft industry, they would live in the shadow of the aero-engine specialists, but would contain the same type of machinery and produce the same products to the same standards as the parent company.

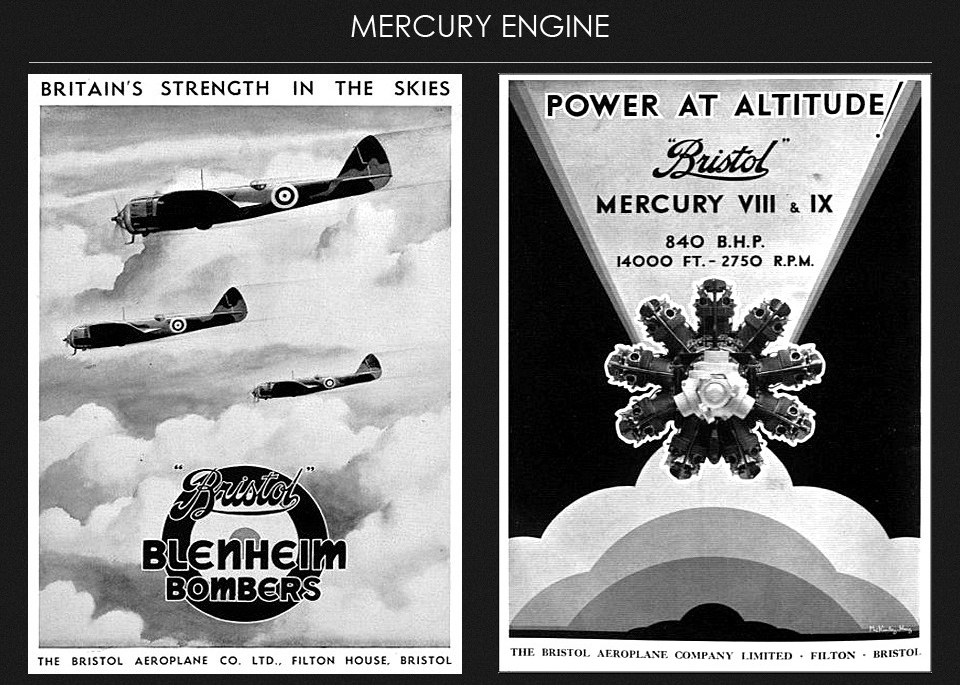

In April 1936 the Air Ministry approached Rover, who by now was a well established company employing a few thousand people. The proposal by the Air Ministry was that a new factory would be built by the Government but ran by Rover at Acocks Green, Birmingham. Rover would initially produce parts for the Bristol Aeroplane Company's Mercury and Pegasus radial engines, used in many of the RAF's planes at that time. Acocks Green was given the title Rover No.1 Shadow Factory, production was to start at low level and increase to full production in the event of war. Rover No. 1 Shadow Factory started production in July 1937 with deliveries to Bristol starting immedialtey.

By April 1939 all hope of peace with Germany had disappeared, Hitler's invasion of Poland had marked the start of the Second World War. The Shadow Factories were put into full production and once again the Air Ministry approached Rover. The Air Ministry had already made the plans for a second Shadow Factory for Rover, it was to be built on 65 acres of requisitioned farmland north of Solihull, the new Shadow Factory would manufacture complete Bristol Hercules radial engines and employ a workforce of 7,000 people. The new Factory was designated Rover No. 2 Shadow Factory. At three times the size of Rover No.1, it was imperative to begin work at Solihull immediatley in order to reach the completion date. Construction began in June 1939 and the foundations laid a month later, it was during this time Rover took the opportunity to purchase 200 acres of agricultural land adjacent to the new site - a long term move that would pay dividends for Rover's expansion for the future. Rover No. 2 Shadow Factory produced the first components for the Hercules engines 7 months after construction of the new factory begun, the first machined parts were completed in January 1940. The first completely built Hercules engine made by Rover was tested in October 1940.

In May 1940 all car production at Rover ceased, within a month of this, production had switched to airframe components and engine parts and assembly. The body erecting shops were also converted to wing construction for Lancaster and Bristol bombers. Rover did however retain a service facility for its vehicles being used for war business. Up until this point in time, Rover's Shadow Factories were reaching production targets on schedule, but all this was about to change. On the nights of the 14th and 15th November 1940, the city centre of Coventry was almost raised to the ground during two nights of heavy bombing from the Luftwaffe. Rover's St. Helens plant north of the city centre was so badly damaged that production was halted indefinatley.

Rover could not suffer another blow like this, and so dispersal production was implemented, disused cotton mills further north in Lancashire and Yorkshire were converted into production plants. Rover continued to expand its operations, and by 1942 operated 18 factories, six of which were "Shadow Factories" owned by the Government. Its own workforce of 3,780 staff were complimented by an additional 20,000 members of staff employed in the Shadow and Dispersal Factories and contracted work for the Air Ministry.

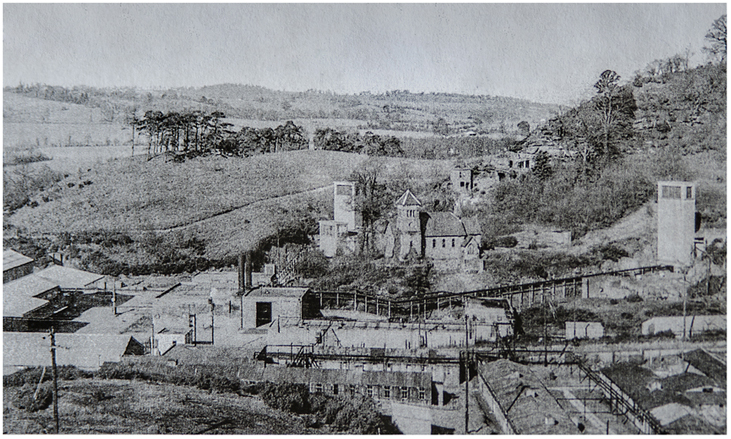

On the 7th June 1941, Major Bulman, Director of engine production for the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP), informed Rover's managing director Spencer Wilkes, that a location for Rover's new Dispersal Shadow Factory had been approved. After the severe bombing on Coventry the previous year and the almost complete destruction of Rover's St. Helens factory, the location of the new factory was to be located underground. This would make it almost impossible for the Luftwaffe to bomb the site, as it would be invisible from the air. A total of 27 sites had been considered before the final decision was made. The site chosen was Kingsford Country Park at Blakeshall Common, near Kinveredge, north of Kidderminster. The new site was designated "Drakelow Underground Dispersal Factory", this was later changed to Rover No.1D Shadow Factory (D=Dispersal), and was intended as a back-up and feeder plant for Acocks Green (No.1 Shadow Factory) and Solihull (No.2 Shadow Factory).

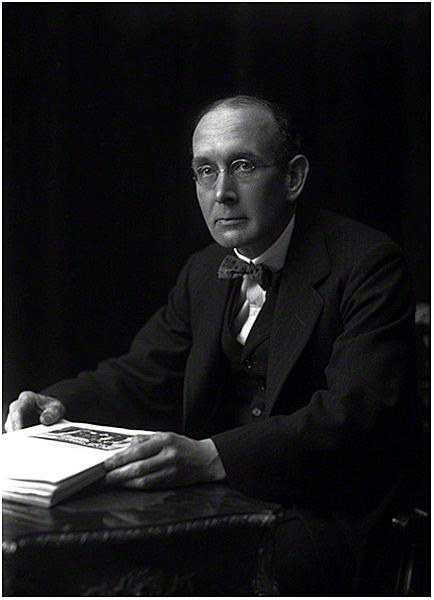

Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners were appointed to the project as consulting engineers and were responsible for the design of the underground factory. Sir Alexander Gibb (12 February 1872 – 21 January 1958) was a Scottish civil engineer with an impressive resume. In 1916 he was appointed Chief Engineer of Ports Construction to the British Army in France, with the rank of Brigadier-General. In 1918 he became Civil Engineer-in-Chief to the Admiralty and the Admiralty M-N scheme, one of his major projects. Then in 1919, he became Director-General of Civil Engineering with the new Ministry of Transport. In 1921 he left government service and became a consulting engineer, founding Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners in the following year. This grew to become the largest civil engineering consultancy in the United Kingdom and was involved in large-scale projects all over the world.

To maximise the stability of the underground factory and ensure maximum efficiency could be achieved when fully operational, the design was kept simple, a grid system accessed by four, 16ft wide main tunnels with19ft wide inter-connecting smaller tunnels known as galleries. At its longest section the tunnels would measure 0.6 of a mile and the width of the complex almost the same, with a total floor space of 284,931 square feet, connected by 3.5 miles (5.6km) of tunnels.

The grid design meant the structural intergity of the complex would not be compromised if hit directly by a bomb. It would also greatly reduce the loss of human life, only certain sections of the complex would be destroyed if hit, with multiple entrances it would also be possible to mount a rescue if needed with out fear of the rest of the factory caving in, production could also be restored quickly.

Once the design was approved the next phase was to begin the excavation of the tunels. The preferred company for many of the Governments construction projects during the war, were Robert McAlpine & Co. Unfortunatley due to their own success and involvement in so many other building projects, they were unable to undertake the work of excavating Drakelow. With McAlpine out of the question the task was then offered to John Cochrane & Sons, who had estimated the entire job would cost £238,000 and take a year to complete.

As the first construction workers arrived at Drakelow it was already evident that due to to the scale of the project, and the amount of workers required to carry out the work, that travelling to and from the site each day would be a problem. Most people in the 1940's did not possess a car and public transport was also limited and costly. The initial solution was to bring in the workforce by trucks and buses from nearby villages and towns, as the work increased and more personnel were required hostels would be built to house the workforce.

Construction commenced at Drakelow in July 1941, Hancocks "Swiss" Village (Rock houses carved into the sandstone), which sat above the construction area had long since been abandoned, as had most of the buildings at ground level. Those that remained were demolished to allow work to commence on the tunnel entrances, and to provide site access. Gelignite was used to blast the entrances of the four main tunnels into the surface rock. Once this was done the task of extending the tunnels to a depth of 8,066ft began, on completion of this, work would begin on the connecting galleries, this would require a further 8,928ft of blasting. Tunnel 2 was the first to be excavated followed by Tunnels, 1, 3 and 4. The explosives used for blasting the tunnels were Polar Amon No.2 and Polar Saxonite No.3 supplied by Nobel Explosives of Scotland. Initially blasting was going well and on schedule, however one small detail had been overlooked. When blasting the entrance to the connecting galleries, the tunnel lost its shape, this meant that to keep an even connection to the main tunnels, additional brickwork would have to be installed. To remedy this small oversight, the entrances to the galleries had to cut by hand with the use of pneumatic chisels to a depth of 6ft. Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners were not happy with this oversight and informed Rover on 6th October 1941, that the galleries may have to be reduced 4ft in width to ensure their structural stability. The advice was noted but not acted upon.

Within a month of Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners warning, tragedy struck. On the 31st October 1941 a section of roof collapsed whilst blasting in Tunnel 1. Mr Harry Depper and two of his collegues were caught in the blast and sadly lost their lives. Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners once again questioned the structural stability of the tunnels, and informed Rover on 14th November that changes needed to be made to the overall layout of the tunnels to make them safe. Later that month the changes were implented, the distance from the galleries to the main tunnels were increased and cross sections modified. The galleries were now self supporting.

On the 14th October 1941, just eight days after Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners first warning to Rover, the Director of engineering at the Ministry of Aircraft Production, Mr Brian Colquhoun had stated that the first 50,000 square feet of space would be completed at Rover No. 1D Shadow Factory Drakelow on the 10th February 1942, and that final completion of the complex would be on 4th July 1942. The dates could possibly be achieved but were optimistic given the recent setbacks and tragic deaths. John Cochrane & Sons, original quote of £238,000 to complete the project was also seeming as optimistic as the completion dates, by this time the costs were in excess of £500,000. Work continued regardless and conveyors were installed into the main tunnels to speed up the process of removing rock and blasting debris.

Not long after the conveyors were installed tragedy struck again, a further four people were killed. The first was a Mrs Mary Ann Brettel, who was accidentally run over by a dump truck belonging to John Cochrane & Sons whilst outside the tunnels, she died not long after due to shock. The next two deaths were that of two construction workers, after a long hard day in the tunnels they decided to ride the conveyor belt out of the complex, unfortunatley they didn't manage to jump off in time and became entangled within the machinery and subsequently died of their injuries. The last reported death was that of Mr. Eric Harold Newman, Mr. Newman was the Security Officer for Goods In & Out, whilst riding his motorbike out of the complex after finishing for the day, he was accidently struck down by Mr. Wilkes, the coach driver that brought the workers to and from the Tunnels each day.

By now the number of onsite personnel had increased so dramatically, that the bus and truck convoys that had brought the workforce to and from Drakelow, was proving far to inadequate and expensive, petrol rationing also caused problems. The solution came in the form of on site working, the current buildings that had been erected were to be adapted into accomodation blocks or dormitories as a temporary solution, until a purpose built hostel could be completed. This became know as the "Camp Hostel". On the 28th November 1942 the first dormitories were ready for use. For married couples, 36 houses had been requisitioned in nearby Stourbridge. On the 5th April 1943, the purpose built "Blakeshall Hostel" was completed. The "Blakeshall Hostel" was divided into 15 dormitories that could accomodate 334 people, in addition to this another building was built adjacent to the Camp Hostel, this housed a Sick Bay, Canteen and Social Club (This building in now the Kingsford Pub), to cater for the needs of the on site workforce.

On the 9th September 1943, the Camp Hostel was visited by the Fleet Air Arm who had plans to transform the hostel into an officer training centre, however these plans were not executed, this is down to the fact that the United States American Air Force (USAAF) also had plans for the hostel. On the 21st December 1943 the U.S. Air Force IX Tactical Command and 318th Station Complement Squadron took control over the Camp Hostel without warning, two days later the Air Ministry took charge of the hostel in an official capacity on behalf of the Americans. The Camp Hostel was now designated U.S.A.A.F. Station 509.

Rover who had not been notified in advance of this, were then informed that they were to vacate these buildings and cease all activity and maintenance of them immediatley. Water and steam produced from within the tunnels however, were still to be piped into the buildings until the 23rd August 1944.

In early March 1944 the former Camp Hostel had been turned into a Radio and Cryptography School for U.S. Military Personnel, with a permanent staff of 110 instructors. Not long after the 6th June 1944 (D-Day), the former Camp Hostel was further transformed into a Teletype School for U.S. Forces, this was short lived though, on the 22nd August 1944 the Teletype School was relocated to Oxfordshire. The day after this, all water supplied by Rover from the tunnels was stopped. As was all of their responsabilities to the other remaining surface buildings, this was now to be handled by the Ministry of Works who would officially take over on the 21st November 1944.

The Blakeshall Hostel was officially closed on the 15th February 1946. In 1954 it was reopened by the Ministry of Health as a research institute, sadly no date has yet to surface to indicate when the Ministry of Health vacated the Hostel. Today the Blakeshall Hostel is the Kingsford Caravan Park.

Rover No. 1D Shadow Factory Drakelow was completed ahead of schedule, although no definitve date is known. In the eight months it took to constuct Drakelow, some 4,455,00 cubic feet of sandstone were removed from Tunnels 1-4 and the connecting galleries, a further 1,620,000 cubic feet of earth was removed outside the complex to provide access for vehicles and surface buildings. The final cost of the project had well exceeded £1,000,000, and also taken the lives of seven people.

By early 1942 the final touches were being applied to the tunnels, the ventilation system was almost complete and the sandstone walls were given three coats of silica and a finishing coat of "Stet" paint to help seal them. On the 18th May 1942, Rover appointed Mr F. Bowden as the production manager at Drakelow, the build up of crucial staff needed to operate the complex had also begun. On the 1st June the first four galleries were complete and were handed over to Rover to begin installing machinery, although this did not happen staight away, Adit "A" was also handed over ten days later. The same month Routes Securities Ltd, were offered 82,507 square feet of space at Drakelow, but after inspecting the complex Routes declined the offer. Rover however kept the space available for any future companies who might require a secure underground storage facility.

The section that Routes had declined, was finally filled eleven months later on the 7th May 1943, when the Royal Air Force's No. 40 Group from RAF Hartlebury moved in. RAF No. 40 Group were Maintenance Command and responsible for all of the RAF's equipment except for bombs and explosives. Drakelow was the ideal location to store valuable aircraft parts and the meer fact it was invisible from the air, meant the chance of the Luftwaffe bombing the complex was virtually non-exhistent. The RAF section was then sealed off from Rover with gates and armed guards, with Adits B & C used as RAF only access. Some of the parts the RAF stored in Drakelow were: Aircraft canopies, tail sections, tail wheels, hydraulic components, aircraft canons and batteries.

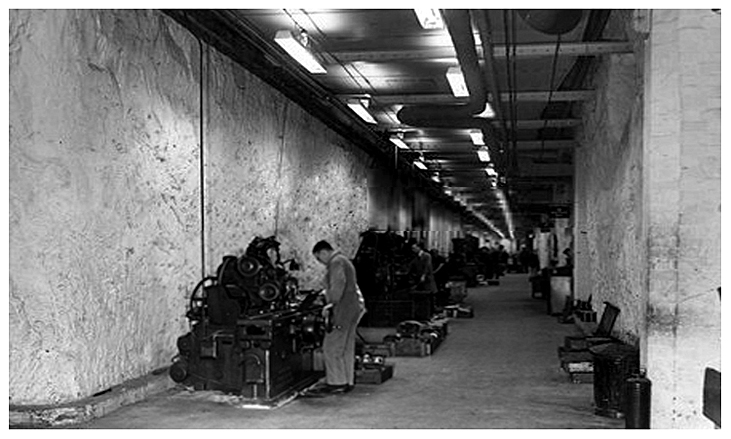

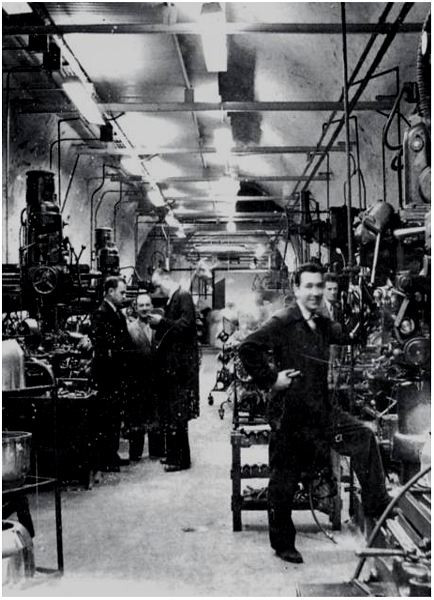

For the next few months Rover increased its workforce and gradually moved into the tunnels section by section, the first machinery was actually installed in late September and early October 1942, although Rover archives have this date down as being the 5th November 1942. Production officially commenced at Drakelow on the 14th October 1942, on the 17th November Rover were officially handed Tunnels 1 & 2 as well of 50,000 square feet of space to begin production. By the 29th November Artic Rod Pins for the Bristol Mercury and Pegasus engines were being manufactured. On the 6th-10th December, Connecting Rods were also being produced. The canteen however was not completed until the 14th December, it was finally opened on the 21st December by Barkers Ltd. Over the following months, production increased as did the parts being manufactured, Gudgeon Pins were being produced from the 4th January 1943 and Cam Sleeves and Valve Caps by the 18th January, by the 25th January Tappets and Valve Cotters were also being machined. Production by now was in full swing, and on the 18th February 1943, the first completed parts were ready to be dispatched. At its peak, Drakelow employed a workforce of nearly 700 people.

What made Drakelow so unique from other Rover Shadow Factories of the time was that it did not assemble aircraft engines, it only manufactured the parts for them. Its primary role was to supply the parts needed for them to: Acocks Green - Rover No.1 and Solihull - Rover No. 2 Shadow Factories, who assembled the full engines. The other unique aspect of Drakelow was that it did not have a production line like a normal factory, instead its manufacturing was displaced throughout the the tunnels with individual lathes, drill's, and presses making up the production line.

Including three car parks and surface buildings, which comprised of: Ventilation Plant, Oil Store, Boiler House, Coal Store, two Sub Stations, Fire Station, Storage Huts, Weighbridge, Air Raid Shelters, Water Tanks, Tropical Packaging Plant and Battery Charging building, Drakelow covered an area of 53.34 acres with a total underground space of 284,931 square feet. The space was divided as follows: Production Area - 56,774 sq ft, Stores - 63,851 sq ft, Welfare / Sick Bay / Office - 17,533 sq ft, Works Offices - 1,838 sq ft, Canteen - 10,050 sq ft, Toilets - 3,625 sq ft, Gangways - 15,429 sq ft and Main Corridors - 32,824 sq ft.

Life in Drakelow Tunnels was made as pleasent as possible for the workforce, working from 7:30am - 5:30pm in a tunnel with artificial light and no windows was not everyones ideal working enviroment, Rover understood this and installed a games room and billiards room adjacent to Sick Bay, to alleviate the stress of working underground, they also dedicated one of the galleries leading to Sick Bay as a Concert Hall, where shows by the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) would perform. Some of the artists who worked for ENSA at the time included: George Formby, Gracie Fields, Vera Lynn and Dora Bryan.

British actress Georgette Lizette "Googie" Withers CBE, AO (12th March 1917 – 15th July 2011) who had a lengthy career in theatre, film, and television, during the war and post-war years performed at Drakelow during the 1940's. Another famous British actor of the time to perform at Drakelow was, Sir John Selby Clements (25th April 1910 - 6th April 1988) famous for starring in British war films such as Convoy (1940), Ships with Wings (1942) and Tomorrow We Live (1943).

Sevaral Bars were also installed in Drakelow, this allowed the workers to unwind after a shift and became a popular hang out. In a further attempt to make life easier for the workforce, Rover gave instructions that from June 1943 music was to played over the Tannoy System, up until now all that could be heard in the tunnels was the banging and crashing of the machines, as they churned out thousand of precision engineered parts hour after hour. When the cheerful tones of George Formby began to pour out of the Tannoy, it was a welcome sound to many and brought a sense of normality. In June the following year, RAF Telephonist Mrs. Vera Churchette, announced weather reports twice a day over the Tannoy System.

On the 14th October 1942, Rover officially started production of aircraft engine parts for the Bristol Aeroplane Company. Bristol radial aircraft engines where at the time, some of the most powerfull and reliable aircraft engines in the world. Listed below in chronological order, are the engines and parts built at Drakelow for Bristol between 1942-1946. Although Drakelow never produced full engines for Bristol, Complete engines of each type were placed in the Tunnels, so the workers could see how the parts they machined fitted in the engine.

The Mercury was a nine-cylinder, single-row, air cooled piston radial engine, designed by Sir Roy Fedden in 1925. It was developed from their Jupiter engine which was fast becoming outdated, initially the Mercury didn't attract that much attention, but the Air Ministry approved three prototypes. Fedden decided against a total new design and instead modified the exhisting Jupiter engine block by reducing its size by one inch. This small adjustment meant the engine could run at higher rpm and was boosted by a supercharger and a reduction gear for the propeller.

The first Mercury was designated: Mercury I followed by varients, II, IIA, III, IIIA, IV, IVA, IVS.2, V, VIS, VISP, VIS.2, VIA, VIIA, VIII, VIIIA, IX, X, XI, XII, XV, XVI, XX, 25, 26, 30 and 31. The finished modifications gave the Mercury 830hp, because of its small size it was originally intended for use in fighters but as the war progressed the engine was modified time and time again, in the end the Mercury was used in both fighters and bombers some of which included: Gloster Gauntlet and Gladiator Fighters and the Bristol Blenheim Light Bomber.

The total number of Mercury engines produced in WWII was 20,700, with 18,224 of them being produced between Rover's Acocks Green - No. 1, Solihull - No. 2 and Drakelow - 1D Shadow Factories. On the 15th April 1943 Rover ceased production of all Mercury engines, although spare parts were still produced by Drakelow for a short period of time after this date.

The Pegasus was a nine-cylinder, single-row, air cooled radial engine, made of aluminium and steel components, designed by Sir Roy Fedden in 1932 and based on the Mercury engine. The Pegasus II was the first engine to be produced by Bristol with 635hp, the Pegasus III with 690hp was the second varient, which was later replaced by the supercharged 1,010hp Pegasus XXII, the final varient was the Pegasus XVIII.

The Pegasus engines were used in the following aircraft: Fairey Swordfish Torpedo Bomber, Short Sunderland Flying Boat, Vickers Wellington Bombers, Bristol Bombay Transport Plane, Anbo 41 Reconnaissance Plane, Saro London Flying Boat, Westland Wallace Biplane and the Vickers Wellesley designed by Barnes Wallis, the inventor of the Bouncing Bomb used by the Dam Busters. The Pegasus engines also set three height records, the worlds longest distance record and for the first flight over Mount Everest.

In total some 32,000 Pegasus engines were produced during WWII, with 12,195 of these being produced between Rover's Acocks Green - No. 1, Solihull - No. 2 and Drakelow - 1D Shadow Factories. On the 15th May 1943 production of all Pegasus engine components was ceased by Rover, although Drakelow continued to produce spare parts for the engines for a short period after this date, just as it had previously done when Mercury production was ceased.

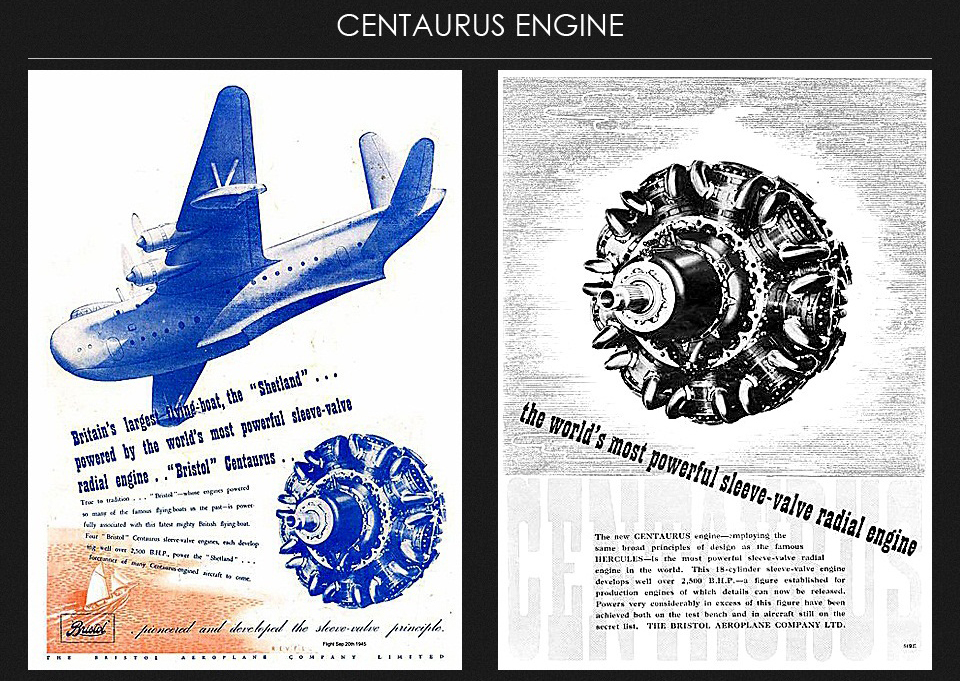

With the end of Mercury and Pegasus program, Drakelow's future was looking quite bleak. Acocks Green - Rover No. 1 and Solihull - Rover No.2 Shadow Factories had since switched to full production and assembly of the new Bristol Hercules Radial Engines, this meant that with all manufacturing of parts being produced by No.1 and No.2 Shadow Factories, Drakelow was technically redundent. Fortunatley, Bristol had developed a new engine, the Centaurus. Again designed by Sir Roy Fedden and originally tested in 1938. The Centaurus like the Mercury, Pegasus and Hercules before it was a derivative of their old Jupiter engine. It would also be Bristol's final engine development during the war.

The Centaurus was an 18 cylinder sleeve valve radial engine capable of delivering 2,000hp - 2,625hp. Sadly the Centaurus program was only short lived. The engine was at the time, the biggest piston engine ever to enter service, the Air Ministry however commented that an engine of this size was not needed at this stage in the war, as most aircraft were designed around housing a 1,000hp engine, although the Hercules was 1,650hp it was better suited to the exhisting airframes of the time. Originally the Centaurus was intended to replace the Hercules engines, but due to the Hercules poor reliability and overheating, all priority had switched back to them in the attempt to make them more reliable.

The Centaurus engines were fitted in the following aircraft during the war: Hawker Tempest Fighter, Vickers Warwick - Maritime Reconnaissance / Transport Plane and Vickers Wellington Bomber. It was also used in a variety of other aircraft toward the end of the war and after. A total of 34 Centaurus varients were produced including the Centaurus I - 2,000hp and the Centaurus 663 - 2,405hp, The most powerful varients were the 170, 173, 660, 661 and 662 which produced 2,625hp.

The Centaurus entered production in 1942 but production at Drakelow did not commence until April 1944. The Artic Rod Setions were to be dispatched by August 1944, at a rate of 30 sets per week until March 1945. In the eleven months of Centaurus production at Drakelow, the parts for some 15,000 engines had been manufactured.

From September 1944 only a month after starting Centaurus production, Drakelow began to receive surplus tools and machines from Acocks Green - No.1 Shadow Factory, it was starting to look like the site would become Rover's strategic storage reserve for tools and machines, The Ministry of Aircraft Production had other plans though. In April 1945 only a month after Centaurus production was ceased at Drakelow, approval was given for the production of the Bristol Hercules Radial Engine parts.

As with virtually every engine from Bristol it was designed by Sir Roy Fedden, the Hercules was a 1,290hp 14 cylinder two-row single sleeve radial engine, first designed by Fedden in 1939. The design was meant to provide optimum intake and exhaust gas flow whilst improving volumetric pressure and improving thermal efficiency in the engine. The Hercules like all of Fedden's engine designs were a derivative on a previous exhisting Bristol engine, in this case the Perseus.

The Hercules was introduced in 1939 as the 1,290hp Hercules I, this was followed by the 1,375hp Hercules II, and mass produced war version Hercules VI capable of delivering 1,650hp. The late war version was the 1,735hp Hercules XVII. The Hercules was fitted in the following aircraft: Bristol Beaufighter, Armstrong Whitworth Glider Tug, Handley Page Halifax Bomber, Saro Lerwick Flying Boat, Short Seaford Flying Boat, Short Stirling Bomber, Vickers Wellesley, Vickers Wellington Bomber and Avro Lancaster B.II Bomber. The Hercules was also used in military and civillian aircraft after the war.

Production of Bristol Hercules parts began at Drakelow in Aprill 1945, by the 16th June the stores were already filled with various components which included spark plug adapters and stationary gear studs, sadly thirteen days later on the 29th June, Bristol informed the Board at Rover that the manufacture of Hercules parts was no longer needed as the contract was to be cancelled. Unfortunatley no records exhist to show how many parts Drakelow produced for the Hercules program.

All manufacturing of aircraft components ceased at Rover No. 1D Shadow Factory Drakelow on the 13th February 1946.

When the Second World War ended on the 2nd September 1945, Drakelow's future was in doubt once again. Back April 1944 only a month after receiving the Centaurus contract, Rover's Managing Director Spencer Wilks had informed the Board that it was no longer viable to operate Drakelow on an economic basis and recommended it be closed idefinatley, the Ministry of Aircraft Production however refused this recommendation, as it was government policy at the time to retain all war factories in case they were needed in the event of future hostilities. It is this policy that gave Drakelow its new lease of life.

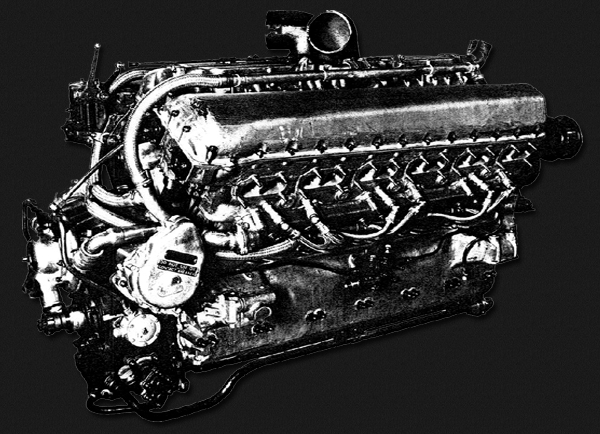

From February 1946 to August 1946 Drakelow served as a storage depot, the Ministry of Supply also stored items but it is unclear what exactly these items were. Machinery, tools and parts that had become surplus to requirements were sent to Drakelow for long term storage from Rover's other Shadow Factories. It's during this period that Drakelow enters its final reicarnation as a Shadow Factory. Back in 1942 Spencer Wilks struck a deal with Lord Hives and Stanley Hooker of Rolls Royce, for the production of a Rolls Royce engine manufactured by Rover. In the late phases of WWII Rover had been involved with Frank Whittle and his Jet Engine Program, Whittle and Rover however did not get on and so it was agreed that Rolls Royce would take over the Jet Engine Program whilst Rover took over Rolls Royce's Meteror engines, a new tank engine derived from the infamous Merlin engine used to power the RAF's Spitfire fighters. On the 14th October 1946 the first Meteor engines arrived at Drakelow and were put into storage.

The Meteor was a V12, 27 litre, 600bhp tank engine designed by Mr. W. A. Robotham of Rolls Royce's Design & Development Division in Belper, Derbyshire. The engine was a simplified version of the infamous Merlin, which powered the RAF's Spitfire fighters during WWII. The supercharger, reduction gear and other parts were removed from the camshaft to simplify its construction, the pistons were also cast rather than forged, and the power output was also dropped to 600bhp.

Up until now, British tank engines had been under powered and unreliable, the Meteor however changed that. The first Merlin engine prepared for tank use, was tried in a modified Crusader in September 1941 at Aldershot. The Meteor was used in the following tanks: Cromwell, Crusader, Comet, Tortoise experimental assault tank and the Conqueror Main Battle Tank.

When the first Meteor engines arrived at Drakelow in 1946, it was thought that production would recommence not long after, sadly this wasn't to be, on the 31st January 1947 the Minsitry of Supply who had already been at Drakelow since 1946, took over the entire complex as a storage depot. Over the next three years a total of 200 Rolls Royce Merlin engines were put into deep storage, as well as Rovers strategic reserve of machines and tools, parts from Vauxhall were also stored within the complex. The influx of items to be stored continued until January 1951.

When Rover first received the order for the Meteor in 1946, production was handed over to Acocks Green - Rover No. 1 Shadow Factory, where Rover had established its Fighting Vehicle Engine Research Establishment (FVERE). Although Rover No.1 was capable of full production and assembly, it made more sense to use Drakelow to manufacture the parts as it had done during the war. In January 1951 production was increased at Rover No. 1 for 20 Meteor engines per week, the Ministry of Supply agreed that Drakelow could be put back into use on a limited scale to assist Rover No. 1. One month later, the order at Rover No. 1 increased to 70 Meteor engines per week, a task that they could not fullfil. Rover informed the Ministry of Supply that in order to achieve this target, Drakelow would need to be put back into full operation.

Rover estimated that to complete the order on time, 552 machines would need to be taken out of storage and refitted in Drakelow, as well as 1,500 staff to operate them. On the 24th April 1951 the Deputy Controller of Munitions Supplies authorized the re-activation of Drakelow but on a limited basis, production officially re-commenced at Drakelow on the 30th April 1951. The small workforce set to the task in hand immediatley and parts started to flow of the machines that same afternoon. Production continued at a small but steady rate until September 1952, when it seems that the parts were becoming surplus to requirments. The surplus stock of parts were then transferred over to the Director of Storage at Drakelow. Unfortunatley for Rover, by June 1953 things had once again changed when it was announced that production of the Meteor engine was to be terminated within the next 18 months.

Production continued at Drakelow over the next few years albeit in a very small capacity, whilst Rover attempted to secure more work. Spencer Wilks approached Bristol who had supplied all the work for Drakelow during the war in an attempt to save the complex, Bristol responded but the work was not enough to save Drakelow. In late 1955 all production work at Drakelow was stopped indefinatley. The entire complex was then handed over to the Ministry of Supply once again, and renamed to the "Drakelow Depot". The Ministry of Supply continued to operate Drakelow until 1958 when the complex was transferred over to the Ministry of Works.

The history on Rover No. 1D Shadow Factory Drakelow, key dates and list of former employees who worked there, is the result of over 20 years of research. Credit for this work and donated material is dedicated to the following people: Please click the White hyperlinks to be directed to their websites.

Mr. Paul Stokes, author of "Drakelow Unearthed" which chronicals the history of Drakelow Tunnels - History.

The former "Friends of Drakelow Tunnels." - History.

The Rover Archives and former employees - History & Photographs.

The Drakelow Tunnels Preservation Trust - History, Documents & Graphics.

Mr. Dave Robinson - Aviation Ancestry - Bristol Aircraft Company Posters.

Mrs. Shaw & Mr. Richard Cruise - Photographs.